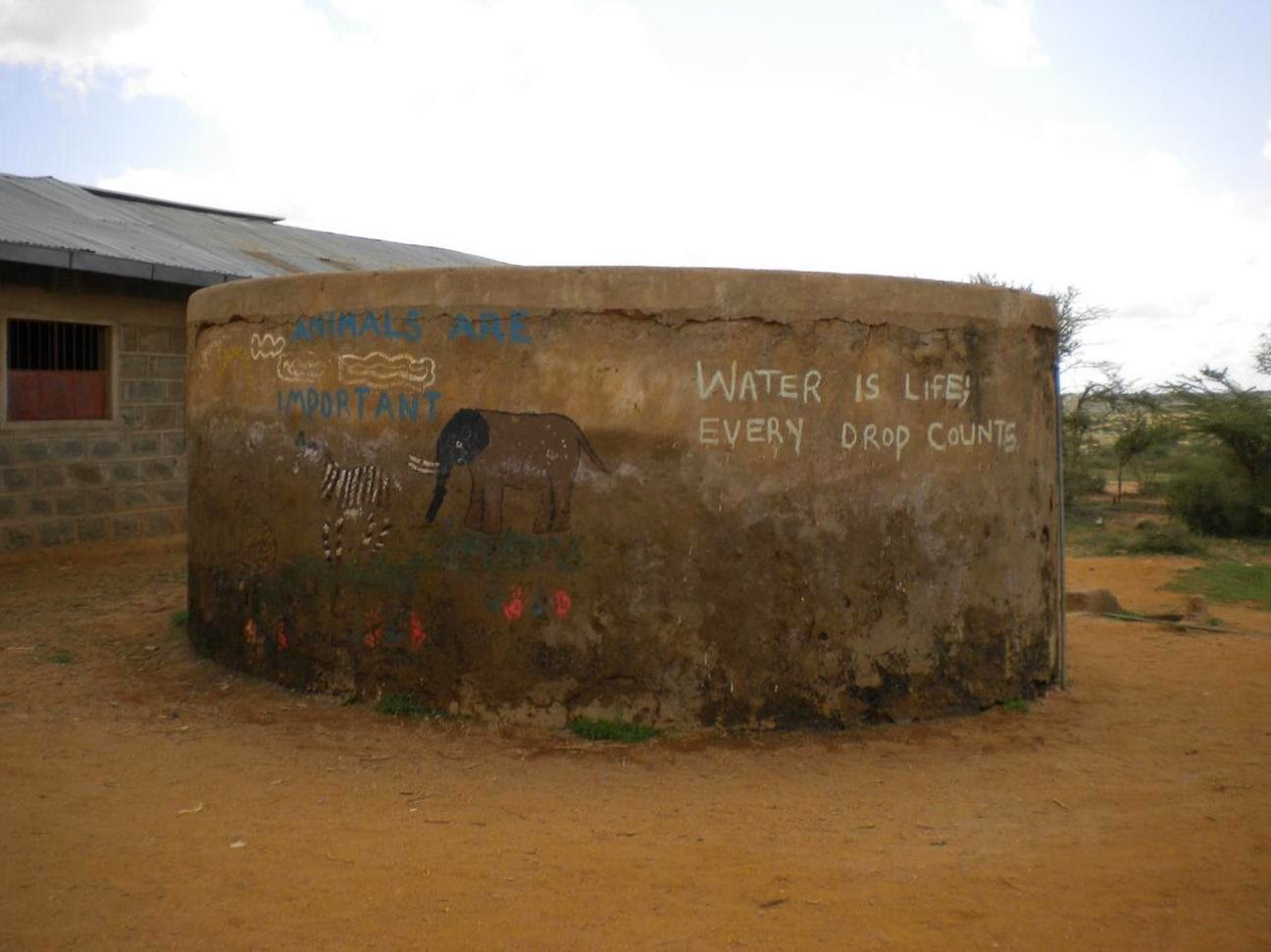

We arrived at Il Motiok Primary School early. The students still had plenty of class time left before the after-school Conservation Club I was there to help teach. Helen and some others left for Nai Perere, and I remained with Nancy and Alex. Nancy Rubenstein is a former elementary school teacher and the wife of Princeton ecologist Dan Rubenstein and the Conservation Clubs are largely their brainchild. Alex is a rising junior interning through the Princeton Environmental Institute as a teacher and she has prepared a lesson on birds and adaptations for this afternoon.

With permission from the Il Motiok teacher, we decided to sit in on a class until school was out. First we caught the tail end of a religious education class in which students were learning causes of suffering (war, sickness, sin, guilt, etc.) and, had time permitted, would have learned of Jesus Christ’s triumph over said suffering. A cursory Wikipedia search reveals Kenya first found Jesus in the form of Portuguese Catholics in the 1400s. Kenya’s colonization by the British from 1920-1963 cemented Christianity’s hold, and today roughly three-quarters of Kenyans are believers. (Other British influences can be found in their Anglicized names and driving on the left side of the road.) I don’t mean to comment on the merits of Christianity; instead, my thoughts drifted to the lasting power of colonialism. Parts of a culture were lost or irrevocably altered due to Western influence. As a white Westerner interacting with young Kenyans, I must be conscious of not overstepping my role.

The next class we saw was a science class. A different teacher went over the parts of the heart and drew a diagram on the board. His style was relaxed and informal, and he actively involved Nancy, Alex, and me (“Let’s ask our visitors what the smallest blood vessels are called”). The students seemed to be enjoying themselves, and I knew I was (“Capillaries!”).

After class, we met up again with the religious education teacher, Joseph, who also teaches the Conservation Club. He expressed discontentment with the way the kids are so often kept silent in their chairs, and declared that for today’s Club we would go on walk.

It was tempting to be frustrated. All the preparation for Alex’s bird lesson just (forgive me) flew out the window. But to be honest I was secretly pleased. Joseph, in the end, is the Club teacher, not Alex, Nancy, or I. If he felt his students had spent too much time inside, well, he knew better than we did.

We walked about 5-10 minutes to a rocky outcropping, past a glut of livestock (domestic goats are everywhere here. Apparently they eat more than their fair share of plants and are bad—dare I say baaaa-d?—for the environment, but between you and me I think they’re hilarious and kind of awesome). I tried to initiate conversation with one or two of the students, but due to their general shyness, unconfident English, or whatever else, I was woefully unsuccessful.

We sat down in the rocks, some of the kids flipping through animal-themed picture books they’d brought along. Joseph began to speak, as much to Nancy, Alex, and me as to the students. He pointed far out in the distance at what he claimed was an elephant, and the students seemed to agree. I’m inclined to believe them, and I think I might have seen it move, but I wouldn’t be shocked to find out it was just a big grey rock.

Elephants at Il Motiok are not quite as beloved as they are in the US. They had trampled and killed a woman three months ago in the area, and such events are not uncommon. While poaching (for ivory) and habitat degradation (especially cutting down trees) have sent elephants onto the endangered list worldwide, there are still quite a few in Il Motiok. Kenya’s textbooks take a pragmatic approach to conservation: elephants are good for tourism, which is good for the local economy, and thus Kenyans should protect their elephants. Joseph explained this to the students in a way that implied they had heard it all before. The tourism benefit might be true in the short term, but I am skeptical that conserving solely for this reason is a sustainable approach.

Luckily, Joseph also hinted at something more important. Discussing leopards, which are endangered due to—yet again—poaching (for their pelts) and habitat degradation (they live in trees), he had his students follow the food chain. “What happens to gazelles when there are no more leopards?” he asked.

The gazelle population, of course, would increase with fewer predators. More gazelles eat more grass, which means less grass left over for the goats, cows, and other livestock upon which human communities depend. (This is a simplification, but the principle stands.) Ecosystems are complex and sometimes fragile things, and humans are a part of them. We should think twice before tampering with the system, because we might bring ourselves down too.

This concept, while not simple, is fairly intuitive in this region of Kenya. Thinking ahead to the eventual object of my project with Helen—the development of a US curriculum—I realize a lot of work must be done with American students. Industrialization and urbanization have created an illusion in the states that the human world and the environment are two separate things. Resource depletion and climate change are showing us just how dangerous this misconception can be, but these threats are less obvious than “my goat shares grass with this gazelle.”

Making the connection between humans and the natural world is hugely important; to save the environment is to save a part of ourselves. I personally feel obligated to point out that even if this weren’t true, I believe we have a moral responsibility to other living things, especially the more intelligent ones like elephants. However, even an anthropocentric ethic is enough to motivate conservation; Helen and I will have to show American students that humans have a place in nature, that Earth is a finite, sensitive home.

When Joseph ran out of things to say, we still had a few minutes left. In honor of the recent inaugural World Giraffe Day, Alex led the kids in a true-or-false-type game with giraffe facts. I let my ecological ruminations slide and watched the game. Honestly, I hadn’t known most of the facts, and I learned a lot. Did you know giraffes can run 50 kilometers per hour? Or that their calves can stand on their own five minutes after birth? These days, it’s easy to attach my knowledge of the non-human world to all this high-minded moral responsibility stuff. I’m glad I haven’t forgotten that it’s also really cool.

With permission from the Il Motiok teacher, we decided to sit in on a class until school was out. First we caught the tail end of a religious education class in which students were learning causes of suffering (war, sickness, sin, guilt, etc.) and, had time permitted, would have learned of Jesus Christ’s triumph over said suffering. A cursory Wikipedia search reveals Kenya first found Jesus in the form of Portuguese Catholics in the 1400s. Kenya’s colonization by the British from 1920-1963 cemented Christianity’s hold, and today roughly three-quarters of Kenyans are believers. (Other British influences can be found in their Anglicized names and driving on the left side of the road.) I don’t mean to comment on the merits of Christianity; instead, my thoughts drifted to the lasting power of colonialism. Parts of a culture were lost or irrevocably altered due to Western influence. As a white Westerner interacting with young Kenyans, I must be conscious of not overstepping my role.

The next class we saw was a science class. A different teacher went over the parts of the heart and drew a diagram on the board. His style was relaxed and informal, and he actively involved Nancy, Alex, and me (“Let’s ask our visitors what the smallest blood vessels are called”). The students seemed to be enjoying themselves, and I knew I was (“Capillaries!”).

After class, we met up again with the religious education teacher, Joseph, who also teaches the Conservation Club. He expressed discontentment with the way the kids are so often kept silent in their chairs, and declared that for today’s Club we would go on walk.

It was tempting to be frustrated. All the preparation for Alex’s bird lesson just (forgive me) flew out the window. But to be honest I was secretly pleased. Joseph, in the end, is the Club teacher, not Alex, Nancy, or I. If he felt his students had spent too much time inside, well, he knew better than we did.

We walked about 5-10 minutes to a rocky outcropping, past a glut of livestock (domestic goats are everywhere here. Apparently they eat more than their fair share of plants and are bad—dare I say baaaa-d?—for the environment, but between you and me I think they’re hilarious and kind of awesome). I tried to initiate conversation with one or two of the students, but due to their general shyness, unconfident English, or whatever else, I was woefully unsuccessful.

We sat down in the rocks, some of the kids flipping through animal-themed picture books they’d brought along. Joseph began to speak, as much to Nancy, Alex, and me as to the students. He pointed far out in the distance at what he claimed was an elephant, and the students seemed to agree. I’m inclined to believe them, and I think I might have seen it move, but I wouldn’t be shocked to find out it was just a big grey rock.

Elephants at Il Motiok are not quite as beloved as they are in the US. They had trampled and killed a woman three months ago in the area, and such events are not uncommon. While poaching (for ivory) and habitat degradation (especially cutting down trees) have sent elephants onto the endangered list worldwide, there are still quite a few in Il Motiok. Kenya’s textbooks take a pragmatic approach to conservation: elephants are good for tourism, which is good for the local economy, and thus Kenyans should protect their elephants. Joseph explained this to the students in a way that implied they had heard it all before. The tourism benefit might be true in the short term, but I am skeptical that conserving solely for this reason is a sustainable approach.

Luckily, Joseph also hinted at something more important. Discussing leopards, which are endangered due to—yet again—poaching (for their pelts) and habitat degradation (they live in trees), he had his students follow the food chain. “What happens to gazelles when there are no more leopards?” he asked.

The gazelle population, of course, would increase with fewer predators. More gazelles eat more grass, which means less grass left over for the goats, cows, and other livestock upon which human communities depend. (This is a simplification, but the principle stands.) Ecosystems are complex and sometimes fragile things, and humans are a part of them. We should think twice before tampering with the system, because we might bring ourselves down too.

This concept, while not simple, is fairly intuitive in this region of Kenya. Thinking ahead to the eventual object of my project with Helen—the development of a US curriculum—I realize a lot of work must be done with American students. Industrialization and urbanization have created an illusion in the states that the human world and the environment are two separate things. Resource depletion and climate change are showing us just how dangerous this misconception can be, but these threats are less obvious than “my goat shares grass with this gazelle.”

Making the connection between humans and the natural world is hugely important; to save the environment is to save a part of ourselves. I personally feel obligated to point out that even if this weren’t true, I believe we have a moral responsibility to other living things, especially the more intelligent ones like elephants. However, even an anthropocentric ethic is enough to motivate conservation; Helen and I will have to show American students that humans have a place in nature, that Earth is a finite, sensitive home.

When Joseph ran out of things to say, we still had a few minutes left. In honor of the recent inaugural World Giraffe Day, Alex led the kids in a true-or-false-type game with giraffe facts. I let my ecological ruminations slide and watched the game. Honestly, I hadn’t known most of the facts, and I learned a lot. Did you know giraffes can run 50 kilometers per hour? Or that their calves can stand on their own five minutes after birth? These days, it’s easy to attach my knowledge of the non-human world to all this high-minded moral responsibility stuff. I’m glad I haven’t forgotten that it’s also really cool.

|

| When it comes to the elephant, students sometimes confuse the words 'endangered' and 'dangerous.' |

|

| My beloved goats |

|

| Seriously goats are everywhere. |

|

| Wild dogs reclaim the streets. |